Released in 1928, The Wedding March, directed by and starring Erich von Stroheim, is a magnificent culmination to von Stroheim’s complex silent film career. Recreating the opulent splendor of Vienna, prior to the Great War, the film is a brilliant critique, of the sharp contrasts between the decaying aristocracy and the struggling lower classes. A radiant Fay Wray, in a memorable co-starring role, gives a powerful performance, vividly conveying the film’s primary narrative theme of love and sorrow. Patrick Miller, Professor Emeritus, The Hartt School, University of Hartford will perform a new live piano accompaniment for the screening. The film will be presented, in a new DCP restoration, by Paramount Pictures Archives, in collaboration with the Library of Congress and Kevin Brownlow.

Ousmane Sembène, one of the greatest and most groundbreaking filmmakers who ever lived and the most internationally renowned African director of the twentieth century, made his feature debut in 1966 with the brilliant and stirring Black Girl (La noire de . . .). Sembène, who was also an acclaimed novelist in his native Senegal, transforms a deceptively simple plot—about a young Senegalese woman who moves to France to work for a wealthy white couple and finds that life in their small apartment becomes a figurative and literal prison—into a complex, layered critique on the lingering colonialist mindset of a supposedly postcolonial world. Featuring a moving central performance by Mbissine Thérèse Diop, Black Girl is a harrowing human drama as well as a radical political statement—and one of the essential films of the 1960s.

Proving once again that the personal is political, French-Congolese documentary filmmaker Alain Kassanda set about to uncover a tumultuous time in his native Congo’s history. His method is both brilliant and unconventional: filming his grandparents as they look back on their lives under Belgian rule, rebellion, and the unavoidable complications of freedom. Kassanda mixes interviews with his family with exploitative Belgian propaganda materials, that were intent on convincing the world – and the Congolese – that the Belgians were the intrinsically superior. Perhaps the most fascinating part of this eye-opening film are the difficult stories of the early days of liberation, and where Kassanda’s grandfather stood on the rise to power of Congo’s first prime minister Patrick Lumumba, a progressive African nationalist who would face a military coup and execution. The result is a brave reckoning not only for the past, but for the present generation and how colonialism continues to shape their identities. “Informative and profound…it highlights the far-reaching wounds of colonization and offers a balm for its scars.” – Concepción de León, New York Times.

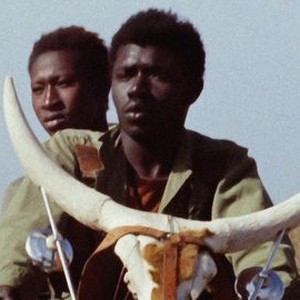

Today, as thousands of young Africans are caught up in emigration to flee poverty and war, Djibril Diop Mabéty’s 1973 film is timely, magical, and fierce. To Mabéty, his homeland of Sénégal – and particularly the slums of Dakar – was still damaged by its years of French rule, plagued with a new ruling class and its own stultifying injustice. Mory (Magaye Niang) is a zebu herder, whose restless dreams sweep him and his moped (adorned with a zebu’s skull and antlers) to the capital city. There he meets a young student named Anta (Marème Niang) who shares his ambition for a stimulating new life in Paris, that “little piece of heaven,” as Josephine Baker sings on the soundtrack. Of course, tickets are expensive, and the couple’s schemes are unsuccessful, until Mory strikes gold by stealing money from an unsuspecting gay man. But even with the treasured tickets in hand, last-minute complications threaten to prevent either one – or both – of the dreamers’ chance of escape. Touki Bouki, now recognized as an inspiration to generations of African filmmakers has been lovingly restored by the World Cinema Project of Martin Scorsese, who calls it “a cinematic poem made with a raw, wild energy… it explodes one image at a time.”

The first feature film by Alice Diop is based on an actual 2015 murder trial in Saint Omer that she attended as a journalist, and would ultimately transform into an award-winning movie. Laurence Coly (as played by the enigmatic Guslagie Malanda). Standing in for the director is Rama, an accomplished journalist sent to cover the trial. Attending every day, Rama discovers a mirror image of herself in the killer. Both share Sénégalese heritage, have difficult relationships with their mothers, are educated, and have French white partners. When Coly calmly reveals that she is not guilty – it is a curse by witches in her tribal village that led her to murder. Where the French secular court sees a flimsy excuse, Rama feels deep in her soul the war between the culture that you grew up with, and the whole new world presented by their former colonizers. Winner, Silver Lion Grand Jury prize, Venice Film Festival. “Brilliant! Diop explores the nature of personal and national identity, the multigenerational trauma of migration, and France’s ongoing failures to reflect its ethnic and racial diversity.” – Richard Brody, New Yorker magazine.

At a time of violent political upheaval in Haiti, April in Paris presents an extraordinary film that explores the conflicted heart of the first country to win independence from their European colonizers in 1803. The inspired collaboration is the work of directors Louis Henderson and Olivier Marboeuf and a group of Haitian artists, actors and poets called The Living and the Dead Ensemble. Ouveratures opens in Paris, where a young man is researching the legendary revolutionary Toussaint Louverture: a former slave who owned slaves himself, who thought of himself as a “free Frenchman,” although he died in a French prison. The film next moves to Haiti, where a group of young performers from Haiti, France and the U.K (The Living and the Dead Ensemble) stage the play Monsieur Toussaint by Édouard Glissant, and translate it into Creole. In the play, ghosts from the Haiti’s past put the dying Toussaint on trial, while illuminating his rare ability both to terrify slave owning countries (including the U.S.), and to inspire enslaved black people to imagine – and fight for – freedom. “A mediation of how the pain and triumphs of a nation’s history are eternal. It is alive, breathing and evolving through the people they influence.”- Gabrielle Pascal, Haitian Times